作者:沪港所&城经所 发布时间:2025-10-27 来源:沪港发展联合研究所+收藏本文

选题人:

那些聪明的年轻人离开了祖国,带着知识和潜力在异国生根,就容易想到“人才流失”。而在哥伦比亚的研究却告诉我们一个不同的故事:这些“海外博士”并不是单向流失的“脑力”,他们更像是活跃在世界科研网络中的桥梁,把国内研究者与全球科学共同体连接起来。

01

为什么海外博士这么重要?

对于像哥伦比亚这样的中等收入国家来说,想要追赶全球的科技前沿,最重要的事之一就是——连上全球知识网络(Barnard et al.,2015;Wagner,2018)。

于是,不少国家会资助优秀学生去海外顶尖大学攻读博士,希望他们带着最新的知识、技能和人脉回来(Dahlman,2010;Fry and Furman,2023)。

听起来很合理,但问题是——要是他们不回来呢?

这就是长期存在的“博士出走困境”:留在国外,是“国家损失”,还是“海外资产”?他们还能不能反哺祖国的科研体系?

越来越多研究其实在告诉我们:这些留在外面的博士并没有“断联”,他们往往组成了强大的侨民网络,能推动知识流动、投资和创新(Agrawal et al.,2011;Saxenian,2005)。有人甚至把这叫作“人才银行”(brain bank)或“人才循环”(brain circulation)——人才不是走了,而是在不同地方流动着,为国家创造新的价值。

02

但问题是:他们真的能带动国内科研吗?

这就是我们(Ito et al.,2025)的研究要回答的问题。我们追踪了 19,000 多名哥伦比亚科学家的职业轨迹,想看看这些“国际博士”究竟有没有把本地研究者带入全球网络。

答案是肯定的——他们确实是科研网络中的关键节点。但是,我们也发现了一个重要的“但”:这些连接不是自动持续的。

它们依赖于这些博士们持续活跃在合作中——只要他们还在那个团队、还在做桥梁,合作就能维系;一旦他们离开,桥就塌了。

03

哥伦比亚的“科学地图”

哥伦比亚是个很适合做这种研究的国家。它投入巨大资金推动科研国际化,资助了数千名博士留学。同时,它的学术履历系统(CvLAC)记录了几乎所有科研人员的详细职业信息,这在全球都相当罕见。

我们将这些数据与奖学金名录、国际论文数据库(OpenAlex)结合,重建了 1990 到 2021 年间哥伦比亚科学家的流动轨迹。由此,我们能区分出三种人:

· 非流动科学家:一辈子都在哥伦比亚读书、工作;

· 流动科学家:在海外取得博士学位;

· 其中包括三类:归国者(永久回国)、侨民(长期留在海外)、以及往返者(两头跑)。

04

谁在真正“连接世界”?

我们发现,只要和这些“流动科学家”合作,本地研究者与外国学者合作的概率会提高约 12 个百分点。

但更有意思的是,这种连接的关键角色并不是“归国博士”,而是那还留在海外或经常往返的科学家。

为什么?因为他们仍在全球科研中心,与国际同行保持活跃联系,手上有资源、有渠道、有机会。简而言之,他们是“站在桥上的人”,随时能把两边的人拉到一起。

05

桥搭起来了,但能自己站住吗?

我们进一步追踪了这些合作的长期效果。刚开始,确实能看到明显的变化:非流动科学家一旦与国际博士合作,他们的国际合著论文数量马上上升,而且合作越多,效果越强。

但当我们排除那些“三方合著论文”(也就是非流动科学家 + 国际博士 + 外国学者)后,情况急转直下——效果几乎完全消失。

换句话说,这些国际博士并没有创造出可以自我延续的新合作,他们更多是在维持一个三方关系:只要他们还在,桥就存在;一旦离开,连接就断。

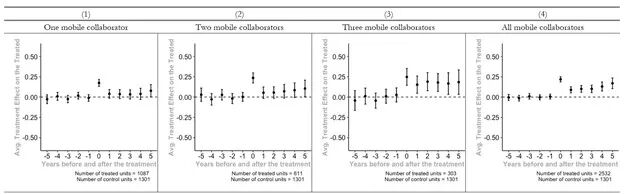

Figure 1: Number of publications with foreign co-authors per year (in logs)

Note: This figure summarises the event study results from Ito et al. (2025). The vertical axis shows the change in the number of foreign co-authored papers for a non-mobile scientist after their first collaboration with a mobile scientist at year 0 (Panel 1). The effect grows and is sustained as they collaborate with more mobile scientists (moving from Panel 1 to 4).

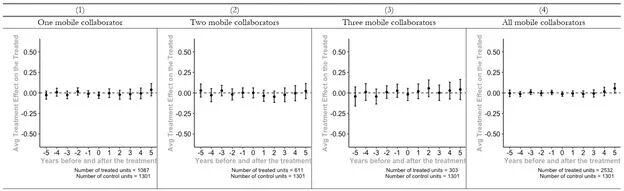

Figure 2: Number of publications with foreign co-authors per year, excluding publications with mobile scientists (in logs)

Note: This figure summarises the results when three-way co-authorships (non-mobile, mobile, and foreign) are excluded. The vertical axis shows the change in the number of foreign co-authored papers for a non-mobile scientist after their first collaboration with a mobile scientist at year 0 (Panel 1). The effect seen in Figure 1 disappears, indicating that the mobile scientist is an essential, ongoing mediator, not just an introducer

06

政策启示:如何让桥更稳?

这个结果其实很有启发意义。它提醒我们,人才流动带来的收益是真实存在的,但需要精心维护。

几个政策方向值得思考:

1. 出国不是“个人投资”,是“系统投资”。

培养出国博士,不只是为了个人成长,而是在为整个科研体系铺设国际连接。

2. 别太急着“逼他们回国”。

侨民与往返博士往往比归国博士更能带来国际资源。过于严格的回国规定,反而可能切断宝贵的学术网络。更灵活的方式是:让他们即便在海外,也能持续参与本国科研。

3. 让桥活下去。

桥不能靠运气,需要维护。可以资助短期访问、国际合作项目,或者建立虚拟平台,鼓励海外科研人员与国内团队长期合作。

07

写在最后

“人才流失”与“人才回流”,其实只是表面的二分法。

在今天这个全球科研高度互联的时代,真正重要的不是人在哪里,而是他们的连接是否还在发挥作用。

哥伦比亚的故事告诉我们:人才不是流失了,而是在流动;关键不是“留”与“回”,而是让那座知识的桥,始终有人在上面行走。

· References

Agrawal, A, D Kapur, J McHale, and A Oettl (2011), “Brain drain or brain bank? The impact of skilled emigration on poor-country innovation,” Journal of Urban Economics 69: 43–55.

Barnard, H, R Cowan, M F de Arroyabe Arranz, and M Müller (2015), “The role of global connectedness in the development of indigenous science in middle-income countries,” in The Handbook of Global Science, Technology, and Innovation, Wiley, 382–406.

Batista, C, D Han, J Haushofer, G Khanna, D McKenzie, A M Mobarak, C Theoharides, and D Yang (2025), “Brain drain or brain gain? Effects of high-skilled international emigration on origin countries,” Science 388(6749): eadr8861.

Dahlman, C (2010), “Innovation strategies in Brazil, China, and India: From imitation to deepening technological capability in the South,” in X Fu and L Soete (eds.), The Rise of Technological Power in the South, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 15–48.

Fry, C, and J L Furman (2023), “Migration and global network formation: Evidence from female scientists in developing countries,” Organization Science.

Ito, R, D Chavarro, T Ciarli, R Cowan, and F Visentin (2025), “From drains to bridges: The role of internationally mobile PhD students in linking non-mobile with foreign scientists,” Journal of Development Economics 177: 103577.

Kim, J (1998), “Economic analysis of foreign education and students abroad,” Journal of Development Economics 56: 337–365.

Müller, M, R Cowan, and H Barnard (2023), “The role of local colleagues in establishing international scientific collaboration: Social capital in emerging science systems,” Industrial and Corporate Change 32: 1077–1108.

Saxenian, A (2005), “From brain drain to brain circulation: Transnational communities and regional upgrading in India and China,” Studies in Comparative International Development 40: 35–61.

Wagner, C S (2018), “The collaborative era in science,” Springer International Publishing.